Corporate governance reforms in India have undergone a significant overhaul since the late 1990s. In 2000, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) introduced the first set of comprehensive corporate governance reforms via Clause 49 of the listing agreement of stock exchanges. Over the next decade, after much debate, voluntary guidelines and lessons learnt through the Satyam scandal in 2009, the Companies Act, 1956 was repealed and replaced by a new set of laws under the Companies Act, 2013. The passage of the 2013 Act was followed by new rules thereunder as well as separate SEBI administered regulations for listed companies.

Since the release of the previous edition of our Handbook on Corporate Governance in India, the country has witnessed significant regulatory changes with continuous refinement of corporate governance standards. Notably, in October 2017, the SEBI formed the Committee on Corporate Governance headed by Uday Kotak (the Kotak Committee) to undertake a comprehensive review of extant corporate governance norms in India. The committee considered several aspects of corporate governance, including corporate purpose and stakeholder interests, and focused on the business realities of Indian corporations, including the dominance of controlling-stockholders. The SEBI’s amended listing regulations reflect many of the recommendations of the Kotak Committee. More recently, in early 2021, the corporate social responsibility (CSR) framework in India has also been significantly amended.

Our Handbook on Corporate Governance in India: 2021 Edition provides a comprehensive study of corporate governance in India. The introductory chapters trace the development of India’s corporate governance regime and examine the nature of ownership and control at Indian companies. Concentrated ownership, often referred to as promoter control, is widespread in corporate India. While concentrated ownership may benefit the corporation and its stakeholders by providing, inter alia, commitment to the performance and growth of the company, it may also lead to exploitation of power. This edition of the Handbook analyzes ownership and control in corporate India through case studies that explore recent challenges faced by Infosys Ltd. and Tata Sons Ltd., two of India’s largest firms. Concentrated ownership and the use of complex group company structures also create the potential for abusive related party transactions that erode value for minority shareholders. With several amendments since passage of the 2013 Act, India’s substantive legal framework for regulating related party transactions has now converged toward international standards.

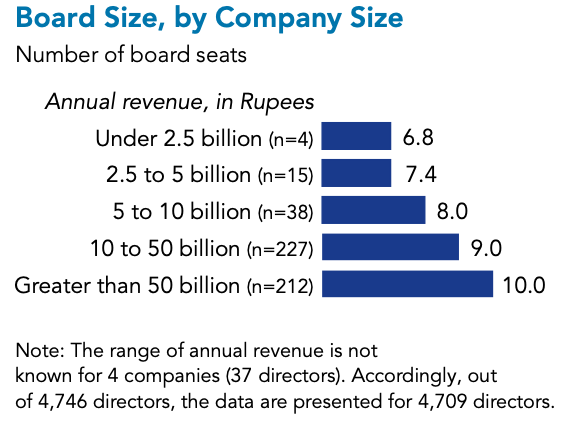

The subsequent chapters of the Handbook delve into the extant corporate governance regime for listed companies, highlighting the key regulatory changes. In the chapter on directors’ duties and board practices, we look into the changing board composition at listed Indian companies. The Handbook presents data indicating the direct correlation between company and board size, for example, certain large companies having as many as ten directors on their boards.

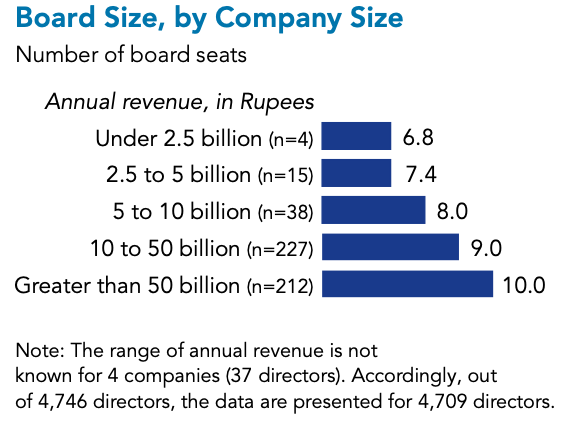

The chapter also highlights how board dynamics have changed at listed Indian companies over the years with women directors and independent directors being onboarded. For example, the Handbook notes that for listed companies in certain sectors (healthcare and information technology), 53 to 55 percent of the board is independent, and that all of the NIFTY 500 companies have one woman director on their boards as mandated by SEBI.

The Handbook addresses the duties and responsibilities of Indian boards and explains director liabilities under Indian law. The Handbook takes a broad perspective on corporate governance, addressing interactions between boards and shareholders, as well as minority and controlling shareholders. Given the growing focus on corporate social responsibility, the Handbook examines the key regulatory changes and debates in India and provides a detailed review of the development of sustainability and responsible business practice norms in India.

The Handbook covers legal duties and their enforcement, as well as ethics and risk management issues. India has strengthened its statutory framework governing ethics through reforms such as recent amendments to the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, the SEBI’s insider trading regulations and the introduction of the National Guidelines on Responsible Business Conduct. The Handbook’s case study of ethical challenges faced by ICICI Bank illustrates the necessary framework for regulating ethical conduct at companies.

Effective corporate governance includes a robust framework for risk management, including board oversight of risk management systems. While the 2013 Act sets forth a limited risk management framework, the SEBI listing regulations include a risk management mandate for listed companies. Accordingly, a company may put in place Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) systems to identify, analyze and evaluate risks, as well as to address cognitive biases in the corporate culture that undermine risk assessment. The Handbook’s case study of the IL&FS Ltd. crisis explicates the shortcomings of ineffective risk management systems.

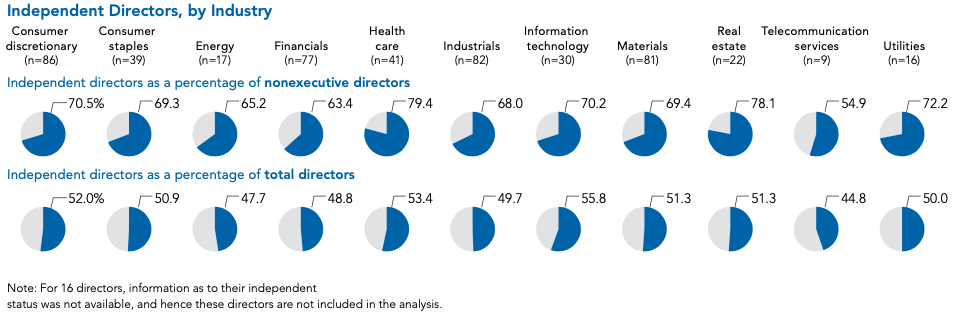

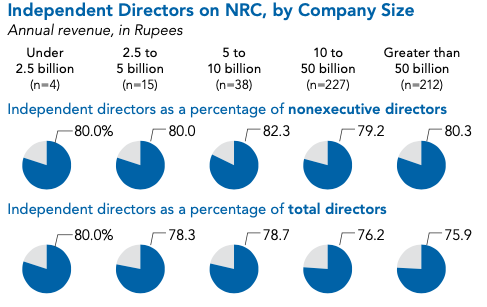

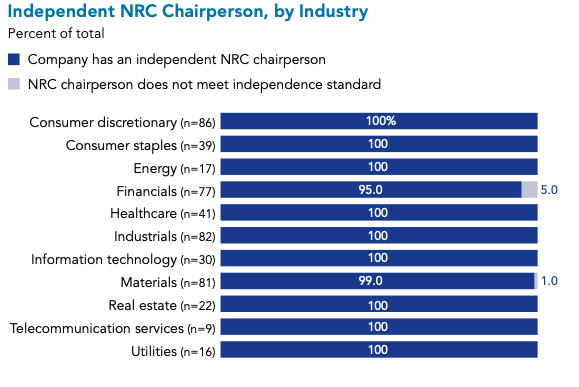

Several chapters address the current legal framework related to board committees—the nomination and remuneration committee (NRC), the audit committee and the corporate social responsibility committee. While SEBI has recently reviewed its mandate on the composition of the nomination and remuneration committee, the Handbook notes that for NIFTY 500 companies, on an average, 80 percent of the directors on the NRC are independent.

Further, except companies in the financials and materials sectors, all NIFTY 500 companies have an independent NRC chairperson.

Given the rise of institutional and other non-controlling shareholders, the Handbook provides an analysis of shareholder participation, activism, and rights under Indian law. The Handbook’s final chapter includes an analysis of the institutional framework and mechanisms for enforcement of corporate governance norms in India. The 2013 Act and the SEBI listing regulations provide several mechanisms by which shareholders may monitor companies as well as enforce their rights. Activism by institutional investors also plays an important role in developing corporate governance standards. Regulatory measures such as the introduction of proxy advisers, facilities for e-voting, and the introduction of class actions can enable non-promoter shareholders to assert their rights. Stewardship codes can encourage institutional investors to focus on companies’ long-term goals and actively monitor public companies on material matters. Collectively, under the 2013 Act, the SEBI listing regulations, and the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, several regulatory bodies have been entrusted with the functions of overseeing the enforcement of corporate governance norms in India. Class action suits, newly introduced under the 2013 Act, allow the National Company Law Tribunal wide powers to grant relief to aggrieved shareholders.

The analysis in the Handbook demonstrates that corporate governance in India continues to evolve as Indian boards face increasingly complex risks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and an expanded regulatory environment. To achieve effective governance, boards must strike a balance between the company’s purpose and operations, while following the highest standards of business ethics and a complex regulatory regime. Through this Handbook, we have highlighted issues that in our view need to be deliberated upon to mitigate future challenges to effective corporate governance.

Afra Afsharipour is Senior Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and Professor of Law at University of California, Davis School of Law.

Manali Paranjpe is Research Associate with The Conference Board in India.

This post relates to the 2021 Edition of Handbook of Corporate Governance in India: Legal Standards and Board Practices, published by The Conference Board in collaboration with global leadership advisory and search firm Russell Reynolds Associate.